‘What we could lose:’ Changes in census could cost ETX millions

Published 3:42 pm Sunday, August 23, 2020

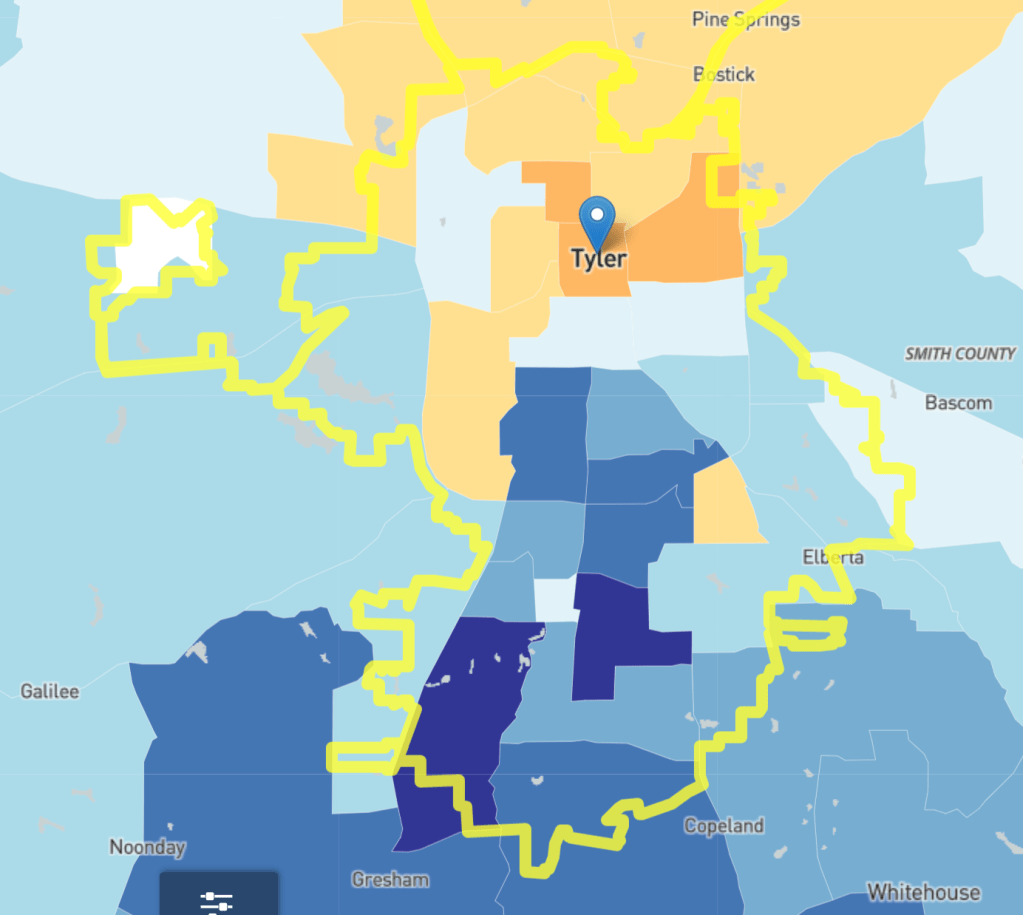

- {span id=”docs-internal-guid-edef451a-7fff-2c36-5454-8a97f4fd3b0a”}{span}Tyler’s response rate disparities are clearly seen in this map; the northern area of Tyler, where more communities of color live, are tracking significantly lower by 10-20 points in response rates than the south of Tyler.{/span}{/span}

Since the last census in 2010, Texas has added about 4 million people — more than any other state — to its population.

An overwhelming percentage of those additions — as much as 87% — are Black, Hispanic and other communities of color, according to the Texas Demographic Center.

These populations are historically considered among the hardest to count.

And that was before a global pandemic and, most recently, an abrupt change in the filing deadline.

Now, demographers and other experts say the Census Bureau’s ability to get a “true and accurate count” for the 2020 census is in doubt — and they fear what an undercount could mean for Texas.

This, they said, was supposed to be the easiest year.

‘The easiest year’

When the census kicked off in Alaska in January, census takers were optimistic.

For the first time, the census made its questionnaire available to take by phone, mail and online — and in 12 different languages. Previously, it could only be completed using a physical form.

Then came the pandemic.

On Jan. 21, the first confirmed case of the coronavirus had arrived in Seattle, Washington.

By mid-March, at the height of COVID-19, the Census Bureau suspended its field operations.

“It (coronavirus) really was the biggest wrench in all of this,” said Lila Valencia, senior demographer at the Texas Demographic Center. “This was supposed to be the easiest census.”

On Aug. 3, another wrench was thrown in the plans — the Census Bureau announced it was shortening its filing date.

The census, which was originally set to end Oct. 31, was now cutting its response period by a full month, with all responses to be filed by Sept. 31.

The schedule change comes at a critical moment in the census’s timeline — the last three months were dedicated to door-knocking, the process that catches some of the hardest to count populations.

Now, that timeframe has been cut by a third. And response rates were already low.

Before enumerators were sent out to begin the door-knocking process in 2010, the response rate for Texas was 64.4%.

As of Tuesday, not even three of every five, or 59%, of households in the state had responded.

And that figure comes even after an entire week of door-to-door visits to homes that had not yet answered the call.

Experts say they’re worried that the “true and accurate count” they’d hoped for is looking less likely with each passing day.

“That’s exactly what we’re worried about,” Valencia said. “The Census Bureau not only has more households that they have to go to and knock on each of those doors, but they’re also having to do that with less time. And that’s why we think it could really result in an undercount — an undercount of the hardest to count communities.”

”The hard-to-count 7 million”

For months, Dr. Jennifer Edwards has been standing at highway intersections, grocery stores and gas stations, holding a sign to remind people to take the census.

“People need gas, they need groceries,” Edwards said. “They can’t ignore me.”

Edwards knew that once the pandemic restrictions were put in place, these essential services would still attract people — and she decided to meet them where they’re at.

“Most of our Carthage residents, they have to go to Longview to get something,” Edwards explained. “Most of our Center residents, they have to go to Shreveport, so I’m getting them at those highway intersections that they can’t avoid.”

Edwards, a Tarleton State University professor, applied for a grant to do census work in three counties in East Texas — Shelby, Panola and Rusk — to promote census taking. She’s also the executive director of the Rural Communication Institute, which serves all of Texas.

Her job is simple, she said: make sure people take the census by informing them of what’s at stake.

“Everyone who is not counted in a household potentially makes that region or makes that county lose up to $6,000 of federal and state funding,” Edwards said. “If you think about a family of four, that is significant.”

Edwards is focused on the 7 million people that are living in “hard-to-count neighborhoods” in Texas — roughly 25% of the population, according to the Texas Demographics Center.

These populations include communities of color, rural Texans, children under five, immigrants, renters and low-income populations. The challenges these populations face are varied, Edwards explained, but it boils down to one simple issue: access.

Those who have not finished the census at the same rate are from “economically disadvantaged communities,” Edwards said.

Most live in government-subsidized housing, nursing homes, or rentals. Low-income families can tend to move more frequently than others, making them hard to track, or they don’t have access to the internet and other services economically advantaged people do, Edwards said.

For others, like rural Texans, access to the internet is unreliable, and those who do have internet often grapple with huge costs or spotty services. Because of this, the census had to hand-deliver census material to many East Texans living in rural areas.

But, unlike many city-dwellers, those in rural areas miss important updates.

“While many of us had received multiple invitations from the Census Bureau reminding us to complete the census, starting in mid-March, many of (rural Texans) didn’t receive that information until two and half months later,” Valencia explained.

Rural Texans and communities of color often have to experience misinformation about the census, Edwards said.

Hispanic populations, she explained, are especially at risk for scams, while rural communities often mistakenly believe the census is not confidential and their information will be shared with other government agencies.

“Rural Texans like their freedom and they do not like a wealth of prying,” Edwards said. “I’ve had to turn our census campaigning into an education piece.”

The East Texas Complete Count Committee, which is made up of leaders from across the region, created sub-committees specific to Hispanic and Latino people, African-Americans and veterans to help address these disparities in self-response.

Nancy Rangel, chair of Smith County’s Complete Count Committee, is also the president and CEO of Hispanic Business Alliance in Smith County.

She has been pushing hard to get East Texas’s Hispanic populations to answer the census — but, she says, they just “don’t feel comfortable” as they have in the past filling out their personal information.

Valencia credits this largely to a push by the Trump administration last year — one that moved to have the question, “Is this person a citizen of the United States?,” listed on the 2020 census.

Critics, Rangel said, saw this move as a way to disenfranchise immigrants living within the United States. Others in the media called it a way to advance the administration’s anti-immigration agenda.

The question was later barred from the census by the United States Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision.

But some experts say even the threat of the question dissuaded a huge swath of Hispanics from completing the census.

That, Valencia said, could be contributing to the undercount in Texas.

Texas has the second-largest number of Hispanics and African-Americans, and the third-largest number of Asian populations of all states in the United States. Texas’s Hispanic population grew by 2 million in the last decade, and that population is on track to be the majority of the state in 2021.

Clusters of older, Black Americans have some of the lowest self-response rates in the region. These populations, Valencia explained, especially in Texas, are where she sees the lowest self-response rate.

“The census is very important for East Texas and East Texans because it enables us to work toward leveling the playing field when it comes to our major metropolitan areas of Texas,” Edwards said. “The Fort Worths, the Dallases, the Houstons, the San Antonios — they receive a lot of federal and state funding. However, our rural Texans count as well. Our rural Texans need access to adequate health care, need access to adequate and stellar education, need access to adequate jobs. We also experience the same struggles as our counterparts in larger cities.”

And if there’s a significant undercount due to the shortened date, East Texas is in jeopardy of losing much of that funding.

”A shortened deadline puts communities at risk”

“We were not expecting it, we really were doing some planning based off of the Oct. 31 date,” Rangel said. “When the date was changed, it affected us greatly as to what kind of planning and goals we had in mind.”

Rangel had planned “a streamline of events” that was meant to bring awareness about the census and its benefits, but because of the coronavirus, the majority of those were canceled. Instead, she’s been pushing public service announcements on TV and radio spots.

She still worries it might not be enough.

“It made it very challenging for us to figure out and design new ways to promote the census deadline that’s coming up, instead of us having now the three months, now we have basically a month short … We would have utilized that whole month to be able to bring more awareness and promote more individuals filling out the census,” Rangel said.

Communities of color, Valencia says, are specifically hurt by the census shortening its filing date. The coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately affected communities of color, from higher death rates to significantly more job losses compared to their white counterparts.

“We know that many of those places in our state where there are larger shares of communities of color, we know that one of the reasons the response rates are lower this time around is because the census is not top of mind,” Valencia said. “They’re trying to meet food and security needs and housing and security needs and making sure that their family stays healthy, as well as having to remember to complete the census.”

Between the pandemic, the economic recession and the shortened filing date, experts are worried that these hardest to count populations — communities of color, low-income families, rural residents — will be significantly undercounted.

“There are billions of dollars that come to the state for programs that are for services like Title I schools, services including child health insurance programs, WIC and food stamps,” Valencia said. “Those who are most of need could also be the ones who lose the greatest services if there’s a severe undercount.”

“A complete and accurate count”

When Jermona Garza, Assistant Regional Census Manager, answered his phone for an interview, he sounded chipper despite the challenges he and his team were facing.

Garza, a native Texan, oversees a wide swath of Texas census-gathering — from Sherman to San Antonio, to Tyler and almost to Midland, as he describes it — but he’s familiar with more than 12 states’ census gathering tactics, he said.

The census, he said, is dedicated to counting “every person once, only once, and in the right place” — despite the filing date being ended a month early.

“We were simply told that the deadline has changed, we’re going to meet that,” Garza said. “We have been very fortunate over the past two years that we’ve had partner specialists in the field, building relationships with nonprofits, the cities, the counties, elected officials, and religious organizations.”

The Census Bureau works with Complete County Committees across the state, much like the one Rangel heads up.

But as the only agency that can do census-gathering, they’re trying to circumnavigate the challenges this year has brought.

To try and combat the spread of the coronavirus, each enumerator that is sent to go door-knocking is equipped with a mask and hand-sanitizer, and other personal protective equipment to give to the home’s residents that they interview.

The census also completed “address-canvassing” last year, which is essentially a way to document every single address in the United States. Census workers are sent to count and collect every address, including those in high-growth areas or where disasters have caused people to leave their homes.

These addresses are put into a massive database that allows the bureau to check if a household has responded to the census. If they haven’t, enumerators are sent to their doors to do the census in person, most likely in their native language.

“We know that Census Bureau staff and personnel are working really hard and have been working really hard since the beginning of the effort,” Valencia said. “But especially once all of the pandemic restrictions were put in place, and really giving them less time to do this work under unprecedented challenges for our country, it could really undermine the level of work that they’ve been putting in.”

Garza says the Census Bureau was permitted to overhire staff to deal with the challenges this year has brought. Already, he says, more Census Bureau employees will be sent into the field to door-knock than they thought they would need when planning in 2019.

“We have always counted every person and been successful in doing so,” Garza insisted. “We will count everyone.”

But the 2010 census tells a different story.

In 2011, Texas’s Mexican American Legislative Caucus filed a lawsuit claiming the census failed to count as many as one-tenth of the Hispanics living in the state. Another statistical database found that the 2010 census undercounted Black populations by more than 800,000.

According to the Texas Demographic Center, Texas’ net undercount was 1% of the population — and figure that could cost the state millions of dollars in funding.

Garza admitted that there were “areas of opportunity” the 2010 census had for counting and that with East Texas’ response rate hovering at 59%, that there are still “opportunities” for counties like Gregg, Harrison and Smith.

“If we could have the timeframe that the Census Bureau had initially requested, we could feel more confident that they’d be able to complete that count during that time,” Valencia said. “But now that that time is being cut short, we don’t know how likely it is that they will be able to do that work.”

“The stakes are huge, and the time is getting shorter.”

Garza says that the benefits of the census can be described in two words: money and representation.

“Billions and billions are returned locally to local cities and counties to do many projects,” Garza explained. “When I say representation, the House of Representatives is reappropriated every 10 years and the number of representatives is based on the number of people living in that state.”

An analysis by the Pew Research Center found that an undercount could leave Texas with one less congressional seat, meaning Texas would only get two additional seats instead of three. But the political power the census gives is not only at a federal level — it trickles to the state and local governments.

Rangel emphasizes to those she speaks to about the census that taking the census impacts East Texas directly because city lines and school districts are also redrawn based on census data.

“If the Hispanics and Latinos want to have someone who is Hispanic or Latino serving on our city council, or some of our other of our city boards, we also need to know that we get counted for,” Rangel said.

More than political power, funding might be the most direct impact citizens will see from the census, Garza explained.

“I’m going to ask three important questions,” Garza said. “Is it important to you that there is a firehouse close to your home? Is it important to you that there is a health clinic or hospital close to your home if needed? Is it important to you that as your children grow up that there is an elementary school within local, walking distance? If you answer yes to any of these questions, then you need to answer the census.”

More than $675 billion in federal funds, grants and support to counties and communities are based on census data. This is money spent on schools, hospitals, public works and federal programs like WIC, SNAP and Head Start programs.

“We use census data to show the needs in our communities,” Edwards said. “If people are not counted on the census, those are individuals who will not be served by the grant funding or by federal and state distributions.”

And there is a need in East Texas, Edwards said.

East Texas is currently experiencing a loss of hospitals and health care facilities at an alarming rate. Panola, Rusk, and Shelby County rank in the bottom 50% for poor health outcomes, social and economic factors and physical environment.

Shelby County, in particular, does not even have a hospital.

Census data can appropriate funds to healthcare programs these counties apply for, giving their citizens access to needed healthcare.

“For cities, for counties, for health facilities, there are programs that they can become eligible for and maintain eligibility for if the census data can help them tell their story,” Edwards said.

Transportation and connection to cities from rural areas is also extremely important for East Texans, Valencia says.

“Funding for that (roads), infrastructure and broadband access is critical to East Texas, regardless of who gets undercounted,” Valencia said.

Non-profits who help East Texans through food insecurity also get federal funding and grants based on census data. Schools get Title I funding, which helps low-income and under-achieving students to close the achievement gap.

An undercount of just 1% in Texas could mean a loss of more than $300 million in federal funding, according to the Texas Demographic Center.

“The stakes are huge, and the time is getting shorter,” Valencia said.

“There’s nothing I can do about it.”

Of the seven counties Tyler Morning Telegraph looked at, only Smith County was near 60%, still 4 percentage points below this comparable time to the 2010 census. It currently has the highest response rate in East Texas.

As of Aug.18, these are the following self-response rates for those counties:

Smith: 59.9%

Gregg: 59.4%

Harrison: 56.1%

Rusk: 51.8%

Panola: 51.6%

Cherokee: 49.9%

Shelby: 44.9%

Parts of all seven counties are tracking in the bottom 20% self-response rate for the 2020 census.

“We are trying to target all of our communities, especially the hard-to-count communities,” Rangel said. “Those communities right now, especially in the past, the numbers and the percentages (of census response rate) have been lower than the rest of the population. We’re seeing those numbers and trends … they’re more in the North part of Tyler.”

Northern Tyler, where many persons of color reside, is tracking 10 points below the 2010 census.

Southern Tyler, which is predominantly white, is tracking 5 points above the 2010 census.

In Smith County’s outskirts, the areas that are 10 points lower than the 2010 census are predominantly rural, like Arp, Overton and Troup.

“Historically we’ve looked at the census as an ‘Oh, well, the people in the city do it, but the people in the outskirts do not,’” Edwards said. “Even in the city of Carthage, we’re seeing completion disparities.”

Northern Carthage is only 5 points below, and southern Carthage, where many low-income families live, is tracking 10 points below the 2010 census.

“In Panola County, we’ve actually beat the 2010 numbers by 4.7%,” Edwards said. “In other counties … we’re still a significant percentage points away from the 2010 census completion percentage.”

The majority of Panola county is in the bottom 20% of the response rate for the census, excluding Carthage.

“I haven’t even worried about it between COVID and the budget,” Panola County Judge LeeAnn Jones said when asked for comment. “There’s nothing I can do about it.”

In Harrison County, where only the area near Hallsville is tracking above its 2010 response rate, Judge Chad Sims was surprised at his district’s low turnout.

“I would’ve thought with people having a little more time on their hands, especially if they’re on unemployment, they might have filled it out,” Simsa said. “So it surprises me a little bit. I thought we’d be well ahead of where we were in 2010.”

He is encouraging his constituents to complete the census, emphasizing the political power that comes with taking the census.

Gregg County Judge Bill Stoudt was unaware the census had been cut a month short.

”When you complete the census, that means you existed.”

On Aug. 17, Harris County signed onto a federal lawsuit that was filed in California to block the Trump administration’s efforts to end counting for the census a month early. On Aug. 19, 67 Texas House of Representatives delegates signed a letter asking that the deadline for the 2020 census be postponed to April 30, 2021.

“Simply put, among all 50 states, Texas has the most to lose from a census undercount and Texans will be poorly served unless we work across party lines to get a complete and accurate count,” the letter from the Texas Legislative Study Group caucus read. “In the past, even in divisive political times, Texans have put such differences aside to do what’s best for the people we represent, and they will be the ones who pay the price if the census shortchanges Texans.”

Edwards said she agrees. She believes the census’s power to linking people to funding is vital for East Texas and it’s prosperity, she said.

“We have homelessness, we have individuals who experience food insecurity, and mental health emergencies,” Edwards said. “We need to be able to provide adequate and steller programs because our rural (East Texan) counterparts count as well.”

But for Edwards, filling out the census is more than just a gateway to funding and political representation. It’s a record of your life, she explained.

She has been able to trace her own family history back to the 1860s just from census data.

“The census is one of our only records to say that we existed,” Edwards said. “It’s important for people to leave their mark on the world, on the U.S. by completing the census. When you complete the census, that means you existed.”

You can complete the census at www.2020census.gov or by calling 844-330-2020.